VIEW IN MY ROOM

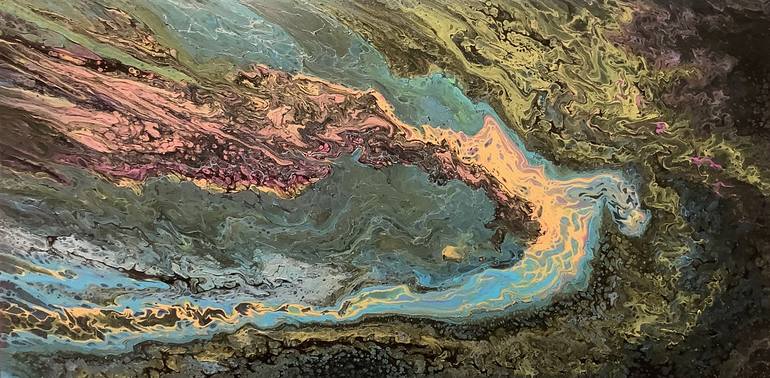

A Sea Dragon Painting

Painting, Acrylic on Canvas

Size: 36 W x 18 H x 0.5 D in

Ships in a Box

Artist Recognition

Artist featured in a collection

About The Artwork

A sea serpent or sea dragon is a type of dragon described in various mythologies, most notably Mesopotamian (Tiamat), Hebrew (Leviathan), Greek (Cetus, Echidna, Hydra, Scylla), and Norse (Jörmungandr). The Drachenkampf mytheme, the chief god in the role of the hero slaying a sea serpent, is widespread both in the Ancient Near East and in Indo-European mythology, e.g. Lotan and Hadad, Leviathan and Yahweh, Tiamat and Marduk (see also Labbu, Bašmu, Mušḫuššu), Illuyanka and Tarhunt, Yammu and Baal in the Baal Cycle etc. The Hebrew Bible also has less mythological descriptions of large sea creatures as part of creation under God's command, such as the Tanninim mentioned in Book of Genesis1:21 and the "great serpent" of Amos 9:3. In the Aeneid, a pair of sea serpents killed Laocoön and his sons when Laocoön argued against bringing the Trojan Horse into Troy. In antiquity and in the Bible, dragons were envisioned as huge serpentine monsters, which means that the image of a dragon with two or four legs and wings came much later during the Late Middle Ages. Stories depicting sea-dwelling serpents may include the Babylonian myths of Tiamat, the myths of the Hydra, Scylla, Cetus and Echidna in the Greek mythology, and even the Leviathan. In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr (or Midgarðsormr) was a sea serpent so long that it encircled the entire world, Midgard. Some stories report of sailors mistaking its back for a chain of islands. Sea serpents also appear frequently in later Scandinavian folklore, particularly in that of Norway. In 1028 AD, Saint Olaf is said to have killed a sea serpent in Valldal, Norway, throwing its body onto the mountain Syltefjellet. Marks on the mountain are associated with the legend. In Swedish ecclesiastic and writer Olaus Magnus's Carta marina, many marine monsters of varied form, including an immense sea serpent, appear. In his 1555 work History of the Northern Peoples, Magnus gives the following description of a Norwegian sea serpent: Those who sail up along the coast of Norway to trade or to fish, all tell the remarkable story of how a serpent of fearsome size, 200 feet [60 m] , or even 400 feet [120 m] long, and 20 feet [6 m] wide, resides in rifts and caves outside Bergen. On bright summer nights this serpent leaves the caves to eat calves, lambs and pigs, or it fares out to the sea and feeds on sea nettles, crabs and similar marine animals. It has ell-long hair hanging from its neck, sharp black scales and flaming red eyes. It attacks vessels, grabs and swallows people, as it lifts itself up like a column from the water. An apparent eye-witness account is found in Aristotle's Historia Animalium. Strabo makes reference to an eyewitness account of a dead sea creature sighted by Poseidonius on the coast of the northern Levant. He reports the following: "As for the plains, the first, beginning at the sea, is called Macras, or Macra-Plain. Here, as reported by Poseidonius, was seen the fallen dragon, the corpse of which was about a plethrum [30 m or 100 feet] in length, and so bulky that horsemen standing by it on either side could not see one another; and its jaws were large enough to admit a man on horseback, and each flake of its horny scales exceeded an oblong shield in length." The creature was seen by Poseidonius, a Philosopher, sometime between 130 and 51 BC. Hans Egede, the national saint of Greenland, gives an 18th-century description of a sea serpent. On July 6, 1734 his ship sailed past the coast of Greenland when suddenly those on board "saw a most terrible creature, resembling nothing they saw before. The monster lifted its head so high that it seemed to be higher than the crow's nest on the mainmast. The head was small and the body short and wrinkled. The unknown creature was using giant fins which propelled it through the water. Later the sailors saw its tail as well. The monster was longer than our whole ship", wrote Egede. On 6 August 1848, Captain McQuhae of HMS Daedalus and several of his officers and crew (en route to St Helena) saw a sea serpent which was subsequently reported (and debated) in The Times. The vessel sighted what they named as an enormous serpent between the Cape of Good Hope and St Helena. The serpent was witnessed to have been swimming with 1.2 m (4 feet) of its head above the water and they believed that there was another 18 m (60 feet) of the creature in the sea. Captain McQuahoe also said that "[The creature] passed rapidly, but so close under our lee quarter, that had it been a man of my acquaintance I should have easily have recognised his features with the naked eye." According to seven members of the crew it remained in view for around twenty minutes. Another officer wrote that the creature was more of a lizard than a serpent. Evolutionary biologist Gary J. Galbreath contends that what the crew of Daedalus saw was a sei baleen whale. A report was published in the Illustrated London News on 14 April 1849 of a sighting of a sea serpent off the Portuguese coast by HMS Plumper. On the morning of the 31st December, 1848, in lat. 41° 13'N., and long. 12° 31'W., being nearly due west of Oporto, I saw a long black creature with a sharp head, moving slowly, I should think about two knots [3.7 km/h; 2.3 mph] ... its back was about twenty feet [6 m] if not more above water; and its head, as near as I could judge, from six to eight [1.8 to 2.4 m] ...There was something on its back that appeared like a mane, and, as it moved through the water, kept washing about; but before I could examine it more closely, it was too far astern — 20px, 20px, "A Naval Officer” Source: Wikipedia

Details & Dimensions

Painting:Acrylic on Canvas

Original:One-of-a-kind Artwork

Size:36 W x 18 H x 0.5 D in

Frame:Not Framed

Ready to Hang:Not applicable

Packaging:Ships in a Box

Shipping & Returns

Delivery Time:Typically 5-7 business days for domestic shipments, 10-14 business days for international shipments.

Handling:Ships in a box. Artists are responsible for packaging and adhering to Saatchi Art’s packaging guidelines.

Ships From:United States.

Have additional questions?

Please visit our help section or contact us.

I’m (I am?) a self-taught artist, originally from the north suburbs of Chicago (also known as John Hughes' America). Born in 1984, I started painting in 2017 and began to take it somewhat seriously in 2019. I currently reside in rural Montana and live a secluded life with my three dogs - Pebbles (a.k.a. Jaws, Brandy, Fang), Bam Bam (a.k.a. Scrat, Dinki-Di, Trash Panda, Dug), and Mystique (a.k.a. Lady), and five cats - Burglekutt (a.k.a. Ghostmouse Makah), Vohnkar! (a.k.a. Storm Shadow, Grogu), Falkor (a.k.a. Moro, The Mummy's Kryptonite, Wendigo, BFC), Nibbler (a.k.a. Cobblepot), and Meegosh (a.k.a. Lenny). Part of the preface to the 'Complete Works of Emily Dickinson helps sum me up as a person and an artist: "The verses of Emily Dickinson belong emphatically to what Emerson long since called ‘the Poetry of the Portfolio,’ something produced absolutely without the thought of publication, and solely by way of expression of the writer's own mind. Such verse must inevitably forfeit whatever advantage lies in the discipline of public criticism and the enforced conformity to accepted ways. On the other hand, it may often gain something through the habit of freedom and unconventional utterance of daring thoughts. In the case of the present author, there was no choice in the matter; she must write thus, or not at all. A recluse by temperament and habit, literally spending years without settling her foot beyond the doorstep, and many more years during which her walks were strictly limited to her father's grounds, she habitually concealed her mind, like her person, from all but a few friends; and it was with great difficulty that she was persuaded to print during her lifetime, three or four poems. Yet she wrote verses in great abundance; and though brought curiosity indifferent to all conventional rules, had yet a rigorous literary standard of her own, and often altered a word many times to suit an ear which had its own tenacious fastidiousness." -Thomas Wentworth Higginson "Not bad... you say this is your first lesson?" "Yes, but my father was an *art collector*, so…"

Artist Recognition

Artist featured by Saatchi Art in a collection

Thousands Of Five-Star Reviews

We deliver world-class customer service to all of our art buyers.

Global Selection

Explore an unparalleled artwork selection by artists from around the world.

Satisfaction Guaranteed

Our 14-day satisfaction guarantee allows you to buy with confidence.

Support An Artist With Every Purchase

We pay our artists more on every sale than other galleries.

Need More Help?